Chapter Books

Picture Books

Co-authored Books

Chapter Books

Picture Books

Co-authored Books

http://www.thehindu.com/books/Goodfellas/article16966377.ece

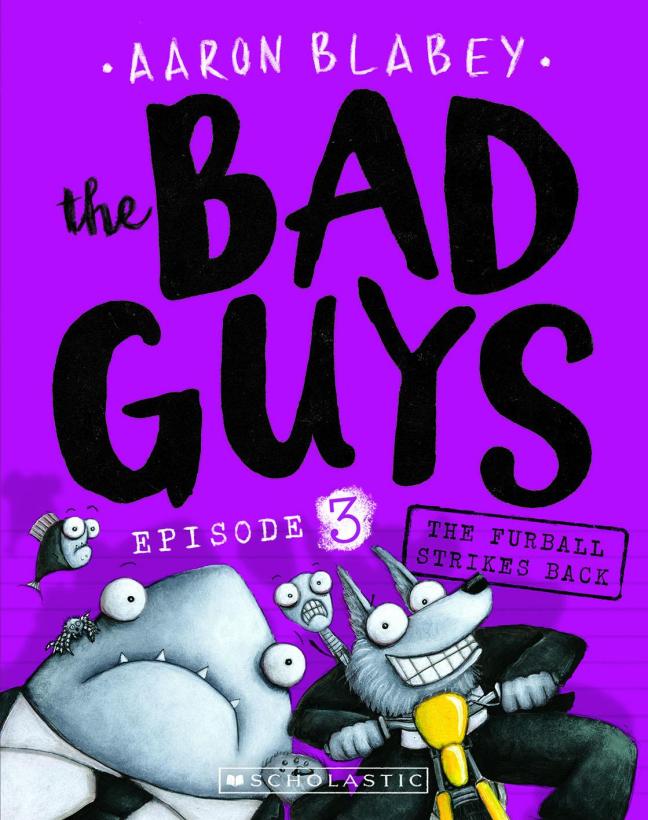

A wolf, a shark, a snake, and a piranha don suits and begin The Good Guys Club. No, that’s not the start of a joke, but the premise of Aaron Blabey’s The Bad Guys series published by Scholastic. The books are about a quartet who really really look like Bad Guys, in fact, everyone thinks they are terribly Bad Guys, scary and dangerous. But what they really really want is to be heroes, especially Mr. Wolf. Unfortunately, everyone keeps judging the Samaritans on how frightening they look, even the dapper suits don’t seem to help their image.

“I wanted to make something that my overly-sophisticated eight and 10-year-olds would think was cool,” said Blabey over email. “It was also a reaction to seeing a lot of deeply boring Early Reader books being brought home from school. Some books seem to have been designed to discourage children from ever wanting to read again. It was my hope to provide an antidote to that.”

Written and illustrated by Blabey, the comic chapter books are fully fun. Each page elicits a few chuckles, and some are simply laugh out loud. No surprise then that The Bad Guys has been extremely successful in Australia and is now available in India as well. “Kids really seem to love it,” said Blabey. “And kids who don’t like to read books are loving it too. THAT is the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. I’m immensely proud of that: kids who consider books to be Kryptonite are queuing up for the next instalment.”

But they are more than just funny stories. In Episode 1, The Good Guys Club sets off to rescue 200 puppies locked up in a maximum security city dog pound (their hopes and dreams are trapped behind walls of stone and bars of steel) and in Episode 2 – Mission Unpluckable, their daring plan is to rescue 10,000 chickens from a high-security cage farm (never mind that one of their members is a notorious chicken swallower). These are narratives that will be loved by animal advocacy champions. “It’s more about characters who’ve simply been judged their whole lives because of the way they look,” said the Australia-based Blabey. “The fact that they’re animals is inconsequential. One of them — Wolf — wants to transcend his situation. His counterpart — Snake — is resigned to it. Their polar approaches to handling this dilemma is the engine of the series.”

The Bad Guys explores attitudes and discrimination at the same time, using humour deftly to present the issues. “I find Wolf heart breaking,” said the bestselling author. “He can’t understand why no one can see how nice he is. The world’s preconceived notions of what the boys are is a rich and satisfying seam of material to mine and for the record, I love making this series more than I can say.”

Blabey effortlessly switches between writing and illustrating comic chapter books and picture books, including the adorable Pig the Pug series and Piranhas Don’t Eat Bananas. Blabey said that his approach to the books is completely different. “I walk when I write picture books. The rhythm of walking helps me write in verse. I walk until I have a book,” he said. “The Bad Guys, on the other hand, is written like a screenplay, sitting at a desk, on a Mac. The process of switching between them is like crop rotation (Joni Mitchell famously referred to moving between song writing and painting in the same way. I’ve stolen that from her.)”

As he walks about the Blue Mountains thinking up his stories, Blabey pens them down on phones and other such entities. “I like mediums of impermanence, like phones, white-boards and napkins, because they encourage naughtiness,” he said. “Handsome notebooks demand reverence. Every mark seems to diminish their beauty. My notes app, on the other hand, feels utterly transient, so I tend to be more relaxed and playful when I write on it. I love white-board too. Nothing is at stake, so I feel free to play.”

http://www.thehindu.com/books/Spinning-a-different-yarn/article16806907.ece

In an interview, Maurice Sendak said, “I don’t write for children. I write, and somebody says, ‘That’s for children!’” Ask most writers, and they will say that as a child, they pretty much read whatever they could lay their hands on, as long as it held their interest. Children enjoy reading all sorts of books. Yes, they read the ones about schools and diaries in school, adventures and misadventures, but they also savour those that traverse the darker side of life that adults often shield them from. It’s a subject that has been the focus of my multifarious conversations over ten days at Children Understand More…!, a workshop-cum-residency organised by The Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan and Zubaan in Santiniketan.

Seventeen writers and illustrators from different parts of the country have been intensely talking, writing, drawing, debating, discussing, and listening everything kid-lit at the workshop. Mentors — writers Payal Dhar and Devika Rangachari from India, and illustrators Ben Dammers and Nadia Budde from Germany — have been sculpting away at the ideas and stories along with the participants, helping shape them into works that engage with the many difficulties of reality. “We have learned a lot as well,” said Budde. “About how people think differently, how they develop ideas.” All these interactions have been bolstered with superlative meals and mishti at the Mitali Home Stay, where we are staying.

Death, climate change, single parenting, religion, family structures, individuality and gender, body image, growing up in a conflict zone, social stigmas and identity are just some of the subjects that are being written about and illustrated at this workshop. “It’s nice to have the chance to move out of thinking about what can I write, will it be published,” said Dhar, the author of Slightly Burnt, a young adult book that explores queerness. “And to be able to give free rein to what you really want to write or illustrate. The constraints have been removed; the participants have carte blanche with a theme, without bothering how adults will react. It’s liberating. It’s almost like taking off your clothes and running down the beach, removing every covering that is there.” Rangachari agreed, adding, “Maybe we will don the covering when we return, but this has been a breather.”

Instead of using images, Bengaluru-based book designer Nia Thandapani is experimenting with typography and lettering to explore identity and how people are given labels by others. “It’s made me question and refresh my practice, and I can see myself taking forward the many conversations and work that’s been going on,” said Thandapani.

Novelist C.G. Salamander and illustrator Sahitya Rani are questioning the academic system through a graphic novel, while Meenal Singh is exploring grief and loss in her story. “It’s been great to see how visual and verbal language works together,” said Dammers. “Writers have seen how text can be represented visually and illustrators are working with the text in an involved manner.”

Samidha Gunjal, an assistant professor at the Symbiosis Institute of Design in Pune, said she had previously attended a similar workshop conducted by Max Mueller and Zubaan, which culminated in the graphic anthology Drawing the Line. “Such workshops provide a platform to share our stories and tell the truth about the current situations to children,” said Gunjal, who is working on two stories, one on manual scavenging with Salamander, and the other on domestic violence.

Karthika Gopalakrishnan, a writer who works for MsMoochie Books in Chennai, has teamed up with Kolkata-based illustrator Shreya Sen to develop a picture book. “Ministry of No is about an eight-year-old girl who is very good at saying no,” said Gopalakrishnan. “The picture book really deals with resilience and family dynamics.”

But what’s truly rare is being able to spend an uninterrupted amount of time in the company of those who care about writing and illustrating for children. “We all work in isolation in this field and as it is, children’s publishing is under-recognised and under-developed here,” said Rangachari, who wrote the historical fiction Queen of Ice. “So it’s a real luxury to have this time and space.”

Shals Mahajan, a Mumbai-based writer-activist, has teamed up with illustrator Tanvi Bhat for a story about Kittu, a child with a peculiarity around his food, and how his family is trying to figure it out. “It’s been a fantastic experience of being in a very peaceful, gorgeous place with a bunch of committed and creative writers and illustrators,” said Mahajan, who wrote the award-winning book, Timmi in Tangles. “It has also been surprisingly very comfortable, and the interaction has been full of camaraderie, which I did not expect. I am really enjoying working with so many people and seeing how they work. I am doing small creative projects with some, with the knowledge that there will be long-term interactions with many.”

Often, in the frenzy of lit-fests, kid-lit is relegated to an inconspicuous corner in the form of workshops or book sales. But now, festivals such as Kahani Karnival, Bookaroo, Peek-a-Book, the Chandigarh Children’s Literature Festival have been offering more curated spaces of storytelling for younger audiences. Then there’s Jumpstart by the German Book Office, which brings together creators of children’s contents in Delhi and Bengaluru for discussions and master classes.

In India, a number of books that explore difficult themes, including sexuality, class, same-sex love, body image, disabilities, and grief, are published, but they are few and far between. The majority continue to be stories about mythology, folk tales, and urban adventure stories. With dwindling brick-and-mortar bookstores, it’s often hard for parents, educators and children to find books with more slice-of-life narratives. But then again, it’s not always easy to find publishers who are willing to back the more difficult themes. Which is why as writers and illustrators of children’s books, it’s sheer joy to be able to step back for a few days, unhindered and uninhibited, to just follow what Dr. Seuss said, “Oh, the thinks you can think!”

https://www.natureinfocus.in/page/why-did-the-leopard-cross-the-road

Here’s a riddle.

Why did the leopard cross the road?

Because she was hungry, and she saw a zebra crossing.

Actually, that’s not true. Unlike us, leopards don’t understand that you need to look first left, then right, then left again, before crossing the road. They don’t know the rules behind the zebra crossing stripes on the road either (honestly, who can blame them, motorists also don’t seem to know that they shouldn’t stand on the zebra crossing; pedestrians have the right of way there). All these rules are made by humans, and it is silly of us to pave a road in the middle of a forest, and then expect leopards or elephants or other animals to know road crossing rules.

Nor do animals get boundaries. Your house or apartment block must have a wall and a gate to mark its perimeter. You know that you can’t just jump into another person’s house (unless you know them) because one, it’s not polite, and two, it’s not safe, and hello, it’s trespassing. But these are man-made boundaries. We don’t ask for permission from forest animals before mowing their trees down to build houses, grow crops, or mine for minerals. According to the World Wildlife Fund’s Living Planet Report 2016, the Global Forest Resources Assessment reports that since 1990, on a gross basis, we have lost a total of 239 million hectares of natural forest!

This means that there is lesser forest cover for animals to call their home, and it’s not that surprising when you hear news of a leopard coming into a school on a Sunday. After all, we can’t expect them to know these man-made boundary walls.

Further, our roads are becoming a point for human-animal conflict. Roadkill — that is wildlife killed on the road by motor accidents — has become a major threat to conservation. A study conducted by Panthera showed that 23 leopards were killed in Karnataka between July 2009 and June 2014 because of road accidents.

In a research paper titled Roadkill Animals on National Highways of Karnataka, by Selvan et. al, the authors conducted a survey to understand how many animals were killed on National Highways NH212 and NH67, which pass through Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka in 2007. They found that 423 animals of 29 species were killed between January and June. Isn’t that awful?

According to the Wildlife Conservation Foundation (WCF), at least three large animals are killed in accidents on these highways. And these include tigers, elephants, leopards, deer, sloth bears, snakes and birds. The good news is that in 2010, the group, with the help of the Wildlife Trust of India and the High Court, was able to ban night traffic in Bandipur. A good thing because 65 per cent of wildlife roadkills until that time were being documented at night.

This is, of course, only Karnataka. But there are so many instances of leopards and other animals becoming victims of accidents — either road or rail — across the country. What can be done about this? Plenty. For instance, not allowing roads or rail networks to be built inside forests or corridors, which animals use to pass from one jungle to another. Many forest departments now have installed neon boards and speed breakers to slow those hurtling vehicles going at top speed in the night. Or like the WCF managed to do — restricting vehicular traffic at night.

The good folks at the Nature Conservation Foundation – India have come up with a fabulous strategy in Tamil Nadu. They have installed seven canopy bridges in the rainforests of the Valparai region — aerial bridges (high up above the ground) that connect tree canopies that were otherwise too far apart across the roads. And it’s already showing results — lion-tailed macaques can cross the road without having to look left, right, and left again, and they don’t have to get down from their trees and dodge passing traffic.

What else do you think can be done? We’d love to hear from you with your ideas. Write to us at comments@natureinfocus.in

https://www.newslaundry.com/2016/12/05/leopard-in-gurugram-how-the-media-made-a-mess-of-a-tragedy

Did you know leopards actually prefer to stay away from human settlements rather than prey on them? The recent killing of a leopard in Gurugram shows how damaging sensationalist reporting on the wildlife can be.

On November 25, horrific photographs and videos of a leopard in Mandawar village in Gurugram made headlines across India. Many, including The Times of India, showed a particularly disturbing image of the villagers dragging the leopard by its tail, its head bludgeoned to bloody pulp. Some blurred out the head. Others, such asIndia Today, chose to carry a video of people posing for photos with the dead leopard, and a disclaimer of “disturbing content, viewer’s discretion advised”.

There’s something almost obscene about the show of human triumph in those photographs and an unspoken reiteration of the idea that wildlife and humanity must have a relationship of animosity. Leopards, incidentally, are solitary animals and humans are actually not their traditional prey. So despite the fact that we call them “predators”, as far as we humans are concerned, leopards are not actually bloodthirsty. This is probably why many local legends in different parts of the country see leopards and tigers as protectors rather than predators. Yet, look at the press reports, the story of progress is one of clashes like this one, between man and animal – it’s a war, and humans won this battle.

Sensationalising human-animal conflict in the media serves no purpose, except to make matters worse. If we’re being shown these images for higher ratings or more views and shares, it is a poor excuse. The Ministry of Environment and Forests’ Guidelines for Human-Leopard Conflict Management 2011 edition clearly state, “Media should contribute to diffusing the tense situation surrounding conflict with objective reporting aimed at highlighting the measures to mitigate conflict. Reporting mainly aggressive encounters with leopards can erode local people’s tolerance and worsen the situation by forcing the Forest Department to unnecessarily trap the wild animal due to public pressure.”

Many headlines played a blame game – “Gurgaon villagers beat leopard to death: How the forest department failed to save the animal’s life”, “Leopard enters Gurugram village, attacks 8, beaten to death”. The Hindustan Times headline read, “Leopard killed: As villagers discuss tales of courage, fear of police action looms large” and then went on to say in the body copy, “In the two days since the incident, the event has been embellished with ‘snippets of valour’.” So was encountering the leopard really an act of courage or was it “embellished”? Your guess is as good as mine.

As writers, our lexicon is everything. Bandying about phrases like “leopard on loose” or “beastly attacks” alter perceptions, often dubbing the animal as dangerous and fearsome. “The media has to stop imagining that the mere sighting of a leopard is like a terrorist in the neighbourhood,” said wildlife conservationist Prerna Bindra, who is also a former member of the National Board for Wildlife. “It does not represent conflict, in all probability the cat was living in peace for years, before it was unfortunately spotted. The cat lived in peace, home sapiens couldn’t. What’s appalling is not just beating the creature to death, but posing-in-glee for pictures as though it were some kind of trophy.”

The Indian Express was one of the few outlets to offer restrained reporting, including this story by Jay Mazoomdaar, titled “Spotted a leopard? Back off, stay calm, let it slip away”. Mazoomdaar elaborated that “leopards traditionally live close to people and just because one is sighted does not mean the animal means harm.” As did The Wire, taking an in-depth look at policy decisions when it comes to human-wildlife conflict. “Leopards tend to live near people,” wrote Neha Sinha for the The Wire. “In modern times, on the other hand, they have vanished from more than 60 per cent of their historic range worldwide. Thus, of all man-animal conflicts, leopards have borne the worst brunt, and the story is no different in India.”

This is not the first instance of man-animal conflict that has been reported in the media. It will also not be the last, in fact climate change will possibly exacerbate it. As will policies such as the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change declaring certain wildlife species as vermin if they are “damaging human life or property”, and translocating leopards (which stresses them further) or projects that mow down forests to make way for roads and highways.

As India moves rapidly towards an economic growth that is bolstered by unchecked development paradigms that shrink forests, it also unravels the fragile bond that humans and wildlife share. What was once a relatively peaceful existence is now marred with violent conflict. In a story, Learning to live with leopards, ecologist Vidya Athreya who has done substantial research on the subject, said “…we are finding that we can share our space with leopards when we know how they behave and we understand how we should behave. In rural India, wildlife is a fact of life; by learning to live with it, we can minimise trouble.”

Efforts are being made to inculcate better understanding in the media. In 2015, the Wildlife Conservation Society India held collaborative workshops with the media on reporting human-wildlife interactions accurately and responsibly. There are numerous documents and publications available online about standard operating procedures as well as guidelines. That can propel nuanced journalism which takes into account multiple perspectives, facts, and relies on wildlife experts and scientists to report on incidents such as this.

Unfortunately, there’s an ingrained sense of fear towards the creatures of the wild that gets exploited in sensational reporting of the kind we saw in the Gurugram leopard case. But this fear mongering doesn’t actually help us come to an understanding of how we’re going to share space with wildlife. And as we bludgeon our way to progress, we’re going to have to figure out a better way to achieve an equilibrium.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/why-should-grownups-have-all-the-fun/article9242787.ece

As the Jio MAMI 18th Mumbai Film Festival kicks off this week, children and young adults can look forward to seeing a range of acclaimed films especially curated for them as part of the section, Half Ticket. Monica Wahi, who is the founder and director of the Southasian Children’s Cinema Forum has curated the section and says that the section is an attempt to introduce cinema to young children, and encourage them to become cineastes.

This year, Half Ticket will commence with the screening of The Little Prince, an animated adaptation of the 1943 classic by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Directed by Mark Osborne of Kung Fu Panda fame , The Little Prince uses stop-motion and CGI to bring to life the beloved story of an aviator who meets a young prince who lives on an asteroid. Wahi says that they are very proud to be screening this internationally-acclaimed film, also because it has had a limited theatrical release across the world, before it premiered on Netflix in U.S.

Half Ticket will present a slate of 28 films from across the world, including 13 features and 15 shorts. “When you put together a programme, the films must be diverse and yet speak to each other to create a larger story,” says Wahi. “From handmade shorts and indie features like The World of Us or The Blue Bicycle to celebrated big studio productions like Heidi and Fanny’s Journey there is a wide range of films.” Apart from the film screenings, nine budding writers will attend a screen writing workshop by Dibarkar Banerjee, Diya Mirza, and Varun Grover.

Half Ticket was introduced last year with schools being its primary audience, and Wahi said that both children and teachers enjoyed the festival immensely. This year, in its second edition, the section is not limited to schools — it is also open to festival delegates accompanied by children and young adults, aged five to 17, for weekend shows. What’s fabulous about the selection is that there’s something for all age groups. Younger children can experience two interactive sessions of animated shorts led by Gillo Theatre Repertory.

Schools too are excited about Half Ticket, and many teachers have expressed an interest on engaging with world cinema across the school year. “This is the kind of impact we hope for,” says Wahi, adding, “When films are no longer looked at as just entertainment content for consumption, but are valued as art, education and culture.”

A lot of the programming is for tweenagers, often the most responsive age group when it comes to new experiences. “At this age, children hunger for something new,” says Wahi. “They are much more open to experimentation, to introspection, and to connect what they have watched inside the theatre to the real world they encounter outside. Introduce them to a new kind of cinema, and they lap it up.” Apart from The Little Prince, Half Ticket will screen films such as Heidi and At Eye Level from Germany, Hang in there, kids! from Taiwan, and Window Horses from Canada. Closer home, children can see Hardik Mehta’s documentrary Ahmedabad ma Famous, Nina Sabnani’s animated short We Make Images and Manas Mukul Pal’s Feature Colours of Innocence among others . Many of these films are difficult to access outside of festivals and Half Ticket offers parents, teachers, and children a space to watch cinema from across the world.

Young adults can look forward to engaging with the films through a series of meaningful conversations and discussions. In fact, for Wahi, one of the highlights of Half Ticket is the discussions that are held with the children, post screening. “We hold discussions with the children, where we deconstruct the films for its artistic and social relevance” she shares. “Every time, I find myself overwhelmed with the kind of responses the children give. Cinema after all is itself a conversation.”

One of the most exciting part of Half Ticket is the children’s jury, which will be comprised of seven children between ages of nine to 17. Last year, the jury unanimously gave the Golden Gateway Award for Children’s Feature to Ottal, a Malayalam film directed by Jayaraj. “ Ottal is a film that’s lyrical and languid. It has a gentle sort of humour and is essentially steeped in sadness. And yet children love it,” said Wahi. The jury choice only underscores the fact that children engage with meaningful cinema, which contrary to popular perception, doesn’t always have to be slapstick or humorous alone.

Wahi adds that the one thing that brings the section together is that the films reflect empathy and openness. “They are about being open and fearless. These films encourage you to empathise with people who are different from you. At the same time, they ask you to be self-critical – compel you to look inside yourself and challenge your own positions. This is very important particularly these days when the world is becoming more and more divisive,” she emphasises.

http://www.dailyo.in/arts/fantastic-beasts-and-where-to-find-them/story/1/14153.html

Newt Artemis Fido Scamander reminds us that without animals, Earth isn’t a place called home.

Newton (“Newt”) Artemis Fido Scamander went down in wizarding history for many of his achievements, including writing the seminal Hogwarts textbook Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them and bringing about the ban on experimental breeding. But after the biopic on him, I think Scamander will, perhaps, be best remembered in the muggle and No-Maj world for his wildlife conservation beliefs.

In the movie Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, magizoologist Scamander (played by Eddie Redmayne) comes to New York in 1926 with a suitcase full of magical creatures. Things begin to unravel when some of these fantastic creatures escape into the city, plus there’s an inexplicable force wreaking havoc at the same time. Fantastic Beasts is a charming film, full of wondrous bits. It’s set in the familiar world of magic, but with a new narrative that also makes a strong case for conservation.

A suitcase packed with wild things

In the eponymous book that JK Rowling published as a Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry textbook in aid of Comic Relief UK in 2001, we first learned about Scamander who, at the age of seven, “spent hours in his bedroom dismembering Horklumps” and then went on to travel across dark jungles, marshy bogs, and bright desserts to learn more about the “curious habits of beasts”. I couldn’t help but imagine Scamander as a cross between David Attenborough and Gerald Durrell. More so, when we got to examine the contents of his suitcase in the movie.The suitcase (spoiler alert) is a world unto itself for magical creatures, and it’s reminiscent of the many animal rescue and rehabilitation centres around the world. Such as the Wild Animal Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre on the outskirts of Pune, managed by The Indian Herpetological Society (IHS) that offers specialised care for injured and orphaned animals, and helps rehabilitate wild animals back into their natural homes. Or Wildlife SOS’s Agra Bear Rescue Facility, a centre for rescued sloth bears. Like Frank – the thunderbird, many of these animals have been trafficked or chained up and some will be returned to their homes in the wild.

Unpacking speciesism in the Anthropocene

In his book, Scamander questions the wizarding world’s earlier attempts at designating non-human magical creatures as “beasts”, as compared to “beings”. “Being”, he says, is a creature worthy of legal rights and a voice in the governance of the magical world. A stark contrast to the idea of speciesism, an idea that humans have greater moral rights than animals.

These are concepts we should reflect upon – as the planet hurtles towards a warmer period that is hastening the loss of biodiversity, as the green light is given for forests (home to the muggle fantastic animals) to be cleared for “development” projects, and as we enter the Age of Extinction for many species. The destruction is apparent, as are its consequences. The year 2016 is set to be the warmest in temperature records since 1880; climate change may be the reason behind the extinction of the small mammal Bramble Cay melomys in the Great Barrier Reef; and in India, we are already looking at horrific pollution levels and unprecedented weather patterns.

In a paper titled “The New Noah’s Ark”, research scientist Ernie Small pointed out that “Most of the world’s species at risk of extinction are neither particularly attractive nor obviously useful, and consequently lack conservation support. In contrast, the public, politicians, scientists, the media and conservation organisations are extremely sympathetic to a select number of well-known and admired species, variously called flagship, charismatic, iconic, emblematic, marquee and poster species.” Another thing that we can take away from Fantastic Beasts.

A friend pointed out that she loved that not all that animals in the movie were cute or even attractive. “Because it sort of drove the point home that you don’t preserve animals just because they’re photogenic,” she said. Whether it’s the enormous erumpent, the luminescent ashwinder, or the fragile bowtruckle, they are all as important for Scamander, like the tree frog, the grey hornbill, and the royal Bengal tiger are for wildlife conservationists.

A case for conservation in the muggle world

In fact, as Scamander writes, “Imperfect understanding is often more dangerous than ignorance”, and that’s often what determines our interactions with nature. Superstitions about unlucky owls, myths of the potency of the rhino’s horn or the fallacy of speciesism has led to owls being injured by stones, birds being imprisoned in tiny cages, and rhinos being poached to near-extinction. When it comes to his fantastic creatures, Scamander says that he hopes to, “rescue, nurture and protect them”, and gently attempt to educate his fellow wizards about them. And let us hope, some Muggles along the way.

Which is what Fantastic Beasts really manages to do – remind us that without these animals, the world would be a much drearier place to live in. Scamander writes that magizoology matters because it ensures that “future generation of witches and wizards enjoy their [fantastic beings] strange beauty and powers as we have been privileged to do”.

Kind of like what Attenborough once said, “It seems to me that the natural world is the greatest source of excitement; the greatest source of visual beauty; the greatest source of intellectual interest. It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living.”

Our planet would be a poorer place without house sparrows taking a dust bath, a funnel web spider spinning her web with a funnel at its centre, or a mother elephant protecting her calf by gently pushing him behind her trunk. Without them, Earth isn’t a place called home.

In this capitalist world, it’s imperative that children learn about financial literacy early on.

http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/Money-Money-Money/article16667863.ece

What do you do when you have to sit down with your child and explain the facts of life? Do you squirm and pass the buck on to your partner or another handy grown-up around you? Or do you sit down and tell it like it is – all the things about bulls and bears, currency exchange, and government regulations? With all the economical chaos that has erupted in the last week, now’s a good time to chat with your children about money and get them financially literate.

Explaining demonetisation

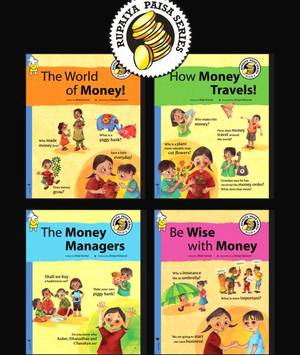

Mala Kumar, Editor at Pratham Books, is the author of the Rupaiya Paisa series, a set of four books that attempts to decode information around money – There’s The World of Money, that takes a look at its history; How Money Travels is about the way transactions happen and the value of currency; Money Managers talks about the people who handle money in our lives; and, Be Wise With Money is about spending, budgeting and government-related plans and insurance. “The ideas for the content for the books were generated during a workshop that included participants from Pratham Books, microfinance company BASIX and other NGOs,” says Kumar. “As a journalist, I was able to collate all the information with valuable inputs from my colleagues. And as an editor and author of children’s books, I was able to sift the mounds of information and present it in byte-sized portions.”

Pratham Books’ aim is to promote reading, and Kumar said that they decided to make financial literacy simple and clear so that young children could enjoy reading and at the same time, imbibe money sense. “Understanding money makes so many things clearer for children – why their parents work, why families do things the way they do, why prudence and thrift are values that families pass on and so on,” explains Kumar. Illustrated by Deepa Balsavar, the four books are a fabulous edition to the library.

When it comes to talking to children about the demonetisation of the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 notes, Kumar offers an easy explanation that parents can use. “Demonetisation involves retiring the existing currency and replacing it with new ones,” she says. “The money is safe, and honestly earned in the form of the old currency that can be exchanged for new notes. Sometimes, this is done when the notes become tattered with use. Sometimes, demonetisation allows governments to ensure that people do not hoard money.”

Encouraging individual opinions

Author Roopa Pai — whose children’s book So You Want to Know About Economicswill be published early next year – says that she wouldn’t get into the debate of right and wrong with children, when it comes to demonetisation. “I would explain why the government thinks it is a good idea and why others think it isn’t, and let them process it in their heads,” she says. “I would talk about the difficulty of executing something as drastic as this in a large country like ours, in which such a large percentage of people still use only cash for all transactions. I would talk about how this kind of thing is easier in other countries because of either political – they are not democracies; or social – they don’t have such large populations, they have more literate populations; or economic – they are almost entirely cash-free and have been for a while – reasons.”

So You Want to Know About Economics , which will be published by Red Turtle, looks at topics such as macroeconomics, microeconomics, trade, taxes and budgets. As a parent, Pai elaborates that she would take her children to the bank to stand in line for an hour or two. This would help them understand the inconvenience felt by people around them and place it in the larger context of the government policy. Pai would encourage them to think how they can help people, such as their household help, who maybe facing a cash crunch. “I would ask them to think about how privileged they are, that they can actually carry on for a long time without using cash at all, and how good it would be for the country if everyone eventually got there,” says Pai, who has also edited a set of math volumes for Pratham Books’ digital platform, StoryWeaver.

Government initiatives

Another way to introduce children to the concept of money is to take them to the Reserve Bank of India Monetary Museum in Fort. It’s a wonderful space for children to understand where their money comes from and its history, currency management in India, and the RBI’s function. The RBI even has a basic microsite, Financial Education, where children can put together jigsaw puzzles of currency notes to understand its design and read short stories. Not the best of designs or concept, but it’s a start, perhaps, especially as it’s available in multiple languages.

Apart from that, the National Council of Educational Research and Training has Personal Finance Reading Materials available online, about the basics of financial planning, investment, and taxes. The website vikaspedia.in has several such examples, including a link to Pocket Money, a financial literacy initiative for students developed by the Securities and Exchange Board of India and National Institute of Securities Markets.

Starting early

Both Pai and Kumar stress the importance of enabling children to take an interest in financial matters. “Financial literacy has to be part of the skills that children learn at home along with other life skills,” says Kumar. “The transfer of knowledge has to be organic. Rather than give them lessons, take children with you when you go to the post office or bank. Help them start a bank account when they turn ten. Allow them to keep and manage their own gift money however small or big the amount is. Maintain a democratic process of discussion and debate around regular family budgets.” Pai recommends talking to children about compounding, the importance of money and how it is earned through hard work, why the government imposes taxes and why it’s vital to pay them, and encouraging them to be entrepreneurs, to earn their own money off school time.

In a capitalistic world, it is increasingly becoming important for parents to ensure their children also grasp the social complexities and the idea of privilege. “I think it’s even more important to weave life lessons into it,” says Pai. “You should save for a rainy day, but how much? There’s nothing wrong in spending the money you’ve worked hard for, but should there perhaps be another column in your Spend-Save account-keeping book, titled ‘Share’? Is it always okay to have premium services for people who can afford it so that you get to stand in shorter lines? Should people have access to the best doctors only because they are able to pay more, or should it be based on the criticality of their illness or whether they stood first in line? Communism has been trashed as a failed system, but is it really that impossible to create a more equitable world in more formal ways? Is money really everything?” It’s imperative the discourse starts early, for children to gain important knowledge as well as formulate their own ideas and thoughts about money.

Students will not just learn wizardly literature but also topics of bullying, democracy, and inclusion.

A couple of weeks ago, I found myself at a hipster coffee joint, chatting with children’s books writers and publishers, and the subject inevitably veered towards children’s books.

Over cups of fragrantly-flavoured latte, we discussed how children’s books tackle a diverse range of subjects – in India and internationally – including themes of environment, gender, sexuality, war, prejudice, and politics. We also agreed that they would make for great classroom reading, and many teachers already use some of these books.

Which is why I was thrilled when I read that the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE), an examination conducted by the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations, will now prescribe some of the more popular children’s books for the English Literature curriculum for the next 2017-18 session.

As an ICSE alumnus, I have fond memories of reading Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles.

When I visited The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, I remembered snippets of classroom conversation about The Diary of A Young Girl.And in my final year, I found The Village by the Sea by Anita Desai compelling, especially as a relative newcomer to Mumbai. These stories have stayed with me over the years, over many other lessons (and it’s been quite a few years).

According to news reports, students will now be studying the Harry Potter series – really, I would have aced this class, got O for Outstanding, rather than T for Troll (that was almost my Math grade).

This means not only will they be reading wizardly literature, but also a narrative that a study, The Greatest Magic of Harry Potter: Reducing Prejudice has shown that children who read these books are more open-minded, and less prejudiced.

The Potter books, which have inspired a generation to take to reading with a gusto, also delve into topics of bullying, democracy, and inclusion. And let’s not forget, it helps to be studying about a boy, who may be The Chosen One, but doesn’t get straight Os or even EEs (Exceeds Expectations for the Muggles) in class always.

Another welcome change from the time when we were told that comics will “spoil your English” is the inclusion of comics such as Tintin, Asterix, Amar Chitra Katha and works by American cartoonist Art Spiegelman.

I hope that it will lead to deliberations about gender representation in comics, the different art styles in graphic novels and contemporary artists, the dominance of Hindu mythology in India, the politics of comics – oh, the possibilities are endless.Closer home, students will get a chance to read Satyajit Ray’s Feluda series, I Am Malala by Malala Yousafzai, and Wings of Fire by Dr APJ Kalam.

There’s now a wide range of Indian literature for children to choose from – whether it’s Simply Nanju by ZainabSulaiman about a differently-abled boy and his classmates, Talking of Muskaan by Himanjali Sankar that explores alternate sexuality, Weed by ParoAnand on Kashmir, or Dear Mrs Naidu by Mathangi Subramanian that looks at privilege and the Right to Education Act. These are just a handful of examples; the shelves are brimming with choices for reading lists.

Sudeshna Shome Ghosh, a consultant editor with Red Turtle welcomed the decision. However, she also pointed out that it would be wonderful if these books weren’t all intended for testing, because if children are only preparing for exams, it can take away the joy of reading.

Perhaps, she added, it would lead to different kind of questions being asked – that are more critical and analytical, in nature.

Further, many of these books are expensive, which means that the administrators will need to figure out how to make them more accessible economically. But it’s a promising step.

Stories can be powerful learning tools – offering students a different way of interpreting the world around them, while keeping them engaged because of their timeless narrative. With more contemporary novels making their way into the curriculum, children will be able to better relate with the stories and their protagonists.

Given that many of these books have been made into movies, like The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien, it would also make for interesting classroom discussions about scriptwriting, critiques, and screen language.

There’s always a possibility that some students may just watch the movies, instead of reading the books for homework. But then again, what about all those plot points that the movies edit out?

Like, the entire storyline between Albus Dumbledore and Gellert Grindelwald in the Harry Potter books was missing from the movie. There just might be a term paper question on that.