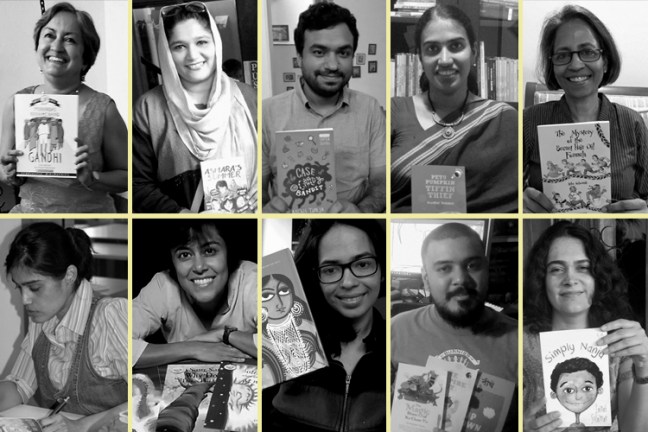

From the balmy weather to the abundant bookshops — there’s much to inspire authors in the city we call home. With some of India’s finest children’s writers living right here, you’ll find places and people you recognise on every page. Meet some of Bangalore’s writers who dream up the loveliest stories for children.

Aditi De

Usually found: Gazing over her computer and out of wide windows which overlook her neighbour’s Singapore Cherry Tree.

It’s hard not to be impressed by an author who has written about some of India’s most iconic figures in her work — including Gandhi in a recent graphic novel, and Nehru as part of the Puffin Lives series. De has a special knack of making her writing both accessible and relevant for children. Reading her life of Gandhi is particularly special because of the attention she pays to his {often neglected} childhood years.

Bibliography: A Twist in the Tale: More Indian Folktales, Jawaharlal Nehru: The Jewel of India, The Secret of the Rainbow Phoenix, and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Reading recommendation: The Mozart Question by Michael Morpurgo

Andaleeb Wajid

Usually found: Writing at her desk, especially when she has time to herself.

Food and slice of life stories come together in Andaleeb Wajid’s books. The Young Adult author has recently written Asmara’s Summer about the very posh Asmara, who much to her horror, finds herself spending a month at her grandparent’s on Tannery Road. If you’ve read Wajid’s books — YA or adult — you will find that Bangalore is a key protagonist in her stories. “All my books feature Bangalore for the simple reason that while I may have travelled to many places around the world, I’ve only lived here,” she said. “This is home and it is predominantly evident in all my books.”

Bibliography: Asmara’s Summer, When She Went Away, The Tamanna Trilogy series, and Kite Strings.

Reading recommendation: The Fablehaven series by Brandon Mull.

Archit Taneja

Usually found: Writing while enduring the long commute from Indiranagar to Whitefield.

For Archit Taneja, who began his writing journey at a workshop organised by Duckbill Books in Chennai, it had to be children’s books because he, “enjoys telling goofy stories that most adults frown upon.” His debut novel for middle readers, The Case of The Candy Bandit, certainly adds a goofy charm to the typical detective story, and the sleuths from the book are ready to take up a new case in the second installment, which will be published soon.

Bibliography: Superlative Supersleuths: The Case of the Candy Bandit.

Reading recommendation: The Selected Works of T.S Spivet

Arundhati Venkatesh

Usually found: Madly trying to make a break through the madness to the relative calm of her desk.

Food is certainly a recurring theme in her books for both younger and middle readers — with characters like Junior Kumbhakarna and Petu Pumpkin, who just love to eat. Her latest release, Koobandhee – The Adventures of Bala and the Book-barfing Monster hit shelves just this month and tackles another theme that’s close to her heart … books! With some sibling rivalry and feminism thrown in for good measure. While she nurtures dreams of writing in the hills à la Ruskin Bond, she can’t imagine doing what she does in any other city than Bangalore.

Bibliography: Junior Kumbhakarna; Petu Pumpkin: Tiffin Thief, Petu Pumpkin: Tooth Troubles, Bookasura – The Adventures of Bala and the Book-eating Monster, and Koobandhee – The Adventures of Bala and the Book-barfing Monster

Reading recommendation: Coraline by Neil Gaiman {if excitement is what you’re after}. Saffy’s Angel by Hilary McKay {which will leave you feeling good} and Vanamala and the Cephalopod by Shalini Srinivasan {takes you into a fantastic world that’s not too far from Bangalore}.

Asha Nehemiah

Usually found: Writing at her home, where many of the windows look out to trees full of birds.

You can’t help but giggle at a title like The Boy whose Nose was Rose and Other Rollicking Stories. But then that’s the magic of Asha Nehemiah’s writing, it’s warm, humorous, little wonder that children love her stories. “I started writing children’s books because it brings together, in the most fun way possible, all the things that are closest to my heart — writing, stories, fantasy, humour, mystery and children!” said Nehemiah.

Bibliography: The Mystery of the Silk Umbrella, Trouble with Magic, The Mystery of the Secret Hair Oil Formula, Zigzag and Other Stories, Meddling Mooli series; The Boy whose Nose was Rose and other rollicking stories, six CBT books — Granny’s Sari, The Runaway Wheel, The Rajah’s Moustache, Wedding Clothes, Mrs Woolly’s Funny Sweaters and Surprise Gifts.

Reading recommendation: Bear Snores On by Karma Wilson, The Why-Why Girl by Mahasweta Devi, Book Uncle and Me by Uma Krishnaswami.

Jane De Suza

Usually found: Sitting at her antique desk contemplating the view out to the sky above her terrace.

A love of detective fiction and a good old mystery guides Jane De Suza’s writing for children, which is characterized by her laid back humour and sense of irreverence. Despairing of the “abominably serious world” kids live in today, she writes, “to get them giggling again” and to show them that, “there’s an equally fun world for the quirky ones, the ones who don’t fit in.”

Even though her Superzero books are set in a fictitious superhero town, don’t be surprised to find elements that you recognise — as everything from her neighbourhood bakery to the slang she hears kids using on the city streets finds its way into her work.

Bibliography: SuperZero, SuperZero and the Grumpy Ghosts, The Party in the Sky, The Big Little Want.

Reading recommendation: From Call of the Wild by Jack London to The Black Stallion by Walter Farley and Marley and Me by John Grogan, to everything by James Herriot, Ranjit Lal and Gerald Durrell.

Roopa Pai

Usually found: Writing in front of her desktop in her room, and when not writing, goes out to enjoy her city.

Although Pai said she started writing children’s books rather late in life, she has contributed stories to magazines, newspapers, workbooks, and textbooks. Pai has gone on to write the brilliant Taranauts series and the extremely popular The Gita For Children, making her one of the most beloved contemporary children’s books writers.

Bibliography: The Taranauts series, The Gita For Children, What if the Earth Stopped Spinning, the Sister, Sister science series, UNICEF’s Children For Change series — Mechanic Mumtaz and Kalyug Sita, Starring Taka-Dimi: My Space, My Body and Frobby and Friends: My Home.

Reading recommendation: Survival Tips For Lunatics by Pakistani writer Shandana Minhas.

Samhita Arni

Usually found: Writing in her study, looking out at trees, with a small chair and an extra cushion for her cat, who keeps her company when she writes.

Samhita Arni started writing children’s books at the age of eight! That was The The Mahabharata – A Child’s View which has since then been published in seven languages and sold over 50,000 copies across the world. The award-winning author has written children’s and adult books including the graphic novel Sita’s Ramayana. “The writing community and events in Bangalore is low-key and down to earth, so much less pressure for me, as a writer and fewer expectations to live up to — which translates into more freedom for me as a writer,” said Arni.

Bibliography: The Mahabharata – A Child’s View and Sita’s Ramayana.

Reading Recommendation: Sorcery and Cecilia or The Enchanted Chocolate Pot by Patricia Wrede and Caroline Stevermer.

Vinayak Varma

Usually found: Writing in his study or rocking chair, late at night or late afternoon, when it’s silent.

Illustrator Vinayak Varma stumbled into writing children’s books purely by accident. Varma wasn’t able to get a sound-mixing internship in 2002, as part of his digital filmmaking course at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology. He ended up ‘begging’ his way into Tulika Books as an intern. During his stint there, Varma proposed an idea about a child learning about weight and gravity by playing seesaw with animals of varying sizes. The result was the lovely picture book Up Down. Since then Varma has illustrated many children’s books, written articles and comics for Tinkle and Amar Chitra Katha, edited the science magazine Brainwave and written and illustrated Jadav and the Tree-Place for StoryWeaver.

Bibliography: Jadav and the Tree-Place and Up Down.

Reading recommendation: All of Asterix and Tintin, which are full of grand adventure, history, humour and excellent visual storytelling. They were easily the most memorable books from my childhood.

Zainab Sulaiman

Usually found: Parked up outside Airlines Hotel, sipping filter coffee and trying to write.

A self-proclaimed ‘old, hard-core Bangalorean’ Zainab Suleiman’s debut novel Simply Nanju was inspired by her time working with differently-abled children at a local school. It’s a gentle, moving read, with characters you really believe in — and whose voices stay with you. You can expect to see lots of Bangalore inspiration in this {and future!} books, keeping in mind that Sulaiman is a loyal city resident who has spent her whole life here.

Bibliography: Simply Nanju

Reading recommendation: Trash! by Anushka Ravishankar, Swamy & Friends by RK Narayan, Little Women by Louisa May Alcott and Calvin and Hobbes. Plus, anything written by Roald Dahl.