http://www.arre.co.in/culture/of-mosquitoes-toes-and-wampfish-roes-roald-dahl-willy-wonka/

Roald Dahl’s birth centenary is a reminder that treats were an essential part of the beloved children’s author’s life – “never too many, never too few, and always perfectly timed.”

A few weeks ago, my family and I were dismayed at the prospect of the Parle Biscuit Factory in Vile Parle shutting shop. When we first moved to Mumbai in the late ’80s, we lived in an apartment block that faced the landmark plant. On most days, we’d abandon our game of Monopoly or our attempts at mugging up Shakespeare to sniff out what was being cooked up at the factory. “It’s Kismi Toffee bars they’re making today,” my mother would say, as a sweet caramel aroma wafted across the railway tracks. Another day, a nutty scent would linger in the air, and we’d agree that a fresh batch of Parle-G biscuits was being baked. Living there was almost like being inside a Roald Dahl book.

So I knew exactly what Charlie would feel like when he’d pass Mr Willy Wonka’s giant chocolate factory on his way to school. “And every day, as he came near to it, he would lift his small pointed nose high in the air and sniff the wonderful sweet smell of melting chocolate. Sometimes, he would stand motionless outside the gates for several minutes on end, taking deep swallowing breaths as though he were trying to eat the smell itself,” wrote Roald Dahl in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in 1964.

Dahl effortlessly captured the luscious aromas and subsequent yearning for melting chocolate, and pinned it down in a book that would go on to become our strongest confectionary-related literary memory. Dahl went so far as to write, “If I were a headmaster I would get rid of the history teacher and get a chocolate teacher instead.” Not surprising coming from a schoolboy who signed up to test chocolate inventions for Cadbury.

On most days, I find myself baking or reading children’s books (so that I can write about them), and in Dahl’s writing, both my enduring interests dovetail. Every time I melt a block of dark chocolate, I think about The Chocolate Room, with its verdant meadows and chocolate river. I hear Mr Wonka say, “The waterfall is most important! It mixes the chocolate! It churns it up! It pounds it and beats it! It makes it light and frothy! No other factory in the world mixes its chocolate by waterfall.”

Like most children growing up during the ’80s, I discovered Dahl’s splendiferous stories only as a teenager. I was growing up on a steady diet of Indrajaal, Archie comics, and Enid Blyton. Dahl came to my neighbourhood library much later, and when I picked up his books as a gangly adolescent, people would look at me all biffsquiggled and wonder why I had never read him before. Once I started though, it was like being on a scrumdiddlyumptious rollercoaster ride for this human bean.

The recipe sounded swatchschollop (as revolting as the title promised): It’s a mix of butter, milk, and yogurt. But the result is surprisingly comforting.

I’m not sure whether it’s the fantastical stories that he spun, of a Big Friendly Giant who caught dreams for children or the horribly hairy Mr Twit with a food-speckled beard. Maybe it was the wondrous words that he conjured up: Over 500 of them from whizpopping to sogmire to mispise, that deliciously roll off the tongue. Or perhaps it was the worlds he dreamt up, where lickable wallpaper, rivers of chocolate, and a peach that’s actually an edible ship are as commonplace as a beanbag in a start-up office. Dahl’s stories are the zozimus (a dream ingredient, for the uninitiated) that childhood should be made up of.

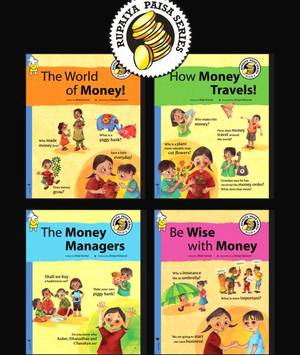

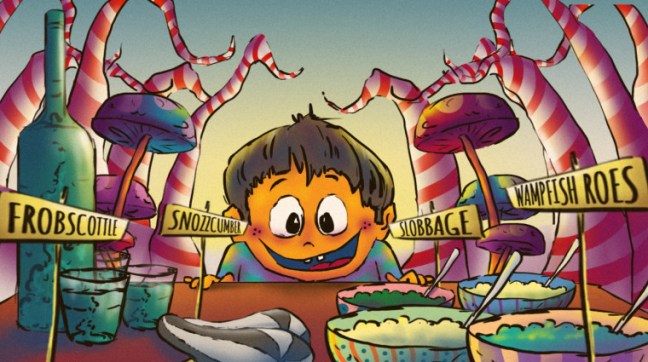

And then there is the food itself – the glorious, scrumdiddlyumptious food. Before molecular gastronomy became something of a trend, Dahl’s stories were already a whizpopping culinary delight. They are replete with familiar foods and mysterious ones, those that had no explanations in the human bean world. But it doesn’t matter, because our imagination fills in the gaps. We were a generation anyway accustomed to reading about scones, ginger pop, and humbugs, without the faintest idea of what they actually looked or tasted like. So it wasn’t hard to imagine what Frobscottle – that fizzy green drink where bubbles sink down rather than rise up – felt like. Even now, tinda and karela distinctly remind me of the ghastly snozzcumber, a knobbly vegetable with black-and-white stripes. All of these were brought alive by Quentin Blake’s illustrations.

Invention was key to these stories. Who else could dream up the concoctions in George’s Marvellous Medicine, full of ingredients such as Golden Gloss Hair Shampoo that was sure to wash Grandma’s tummy nice and clean, and toothpaste to brighten up her horrid brown teeth? It’s remarkable how Dahl knew just what children loved to do: My nephew can spend hours concocting all sorts of potions with coffee beans and water. He looks high and low for bits and bobs to add to it, relishing the results that look more and more vile. Rules, when it comes to invention, must go straight out of the window.

Like this particular ditty from James and the Giant Peach:

I often eat boiled slobbages. They’re grand when served beside

Minced doodlebugs and curried slugs. And have you ever tried

Mosquitoes’ toes and wampfish roes

Most delicately fried?

(The only trouble is they disagree with my inside.)

I don’t know what a doodlebug is, but just the thought of a boiled slobbage is enough to make me want to unwrap a piece of dark chocolate and try to forget about it. Or wickedly threaten my nephew with that when I meet him next. But then perhaps, Dahl was just prophetic, with insects being proposed as staple, resilient food thanks to climate change.

Just as Dahl’s stories were cautionary about the excesses of food, they tackled the grave idea of hunger. As Mr Fantastic Fox’s family go hungry, Dahl describes the anguish the fox parents go through. When the cubs cry from hunger, he writes, “‘How long will it be till we get something to eat?’ their mother didn’t answer them. Nor did their father. There was no answer to give.” Later, Mr Fox says, “Do you know anyone in the whole world who wouldn’t swipe a few chickens if his children were starving to death?”

In The Chocolate Factory, Charlie’s family is so poor that “the only meals they could afford were bread and margarine for breakfast, boiled potatoes and cabbage for lunch, and cabbage soup for supper. Sundays were a bit better. They all looked forward to Sundays because then, although they had exactly the same, everyone was allowed a second helping.” The same book is a lesson in food security: On one hand Dahl writes about poverty and malnourishment, while starkly contrasting it with the “haves” who revel in gluttony, but ultimately are acquainted with the pitfalls of greed. Obesity, in most of his books, was not a trait he loved.

Yet, what’s unmistakable is that so many of the stories are about the joys of food, sharing it, and eating it. And some of the recipes are not even that difficult to pull off. In Roald Dahl’s Revolting Recipes, “an interpretation of some of the scrumptious and wonderfully disgusting dishes” from his books, you will find recipes for Mosquitoes’ Toes and Wampfish Roes made with cod fillets and Lickable Wallpapers made with fruit and gelatine. In the introduction, his wife Felicity Dahl writes, “Treats were an essential part of Roald’s life – never too many, never too few, and always perfectly timed.”

Parsing the recipe book, I couldn’t help but wonder about Butterscotch, which makes the Oompa-Loompas whoop up with joy. The recipe sounded swatchschollop (as revolting as the title promised): It’s a mix of butter, milk, and yogurt. But the result is surprisingly comforting. It didn’t make me tiddly, but it was “tasting as wonderfully of crodscollop”. I replaced the corn syrup in the recipe with golden syrup, and the skim milk with normal milk, and used a blender to mix it all up (the Oompa-Loompas would be scornful of the skim milk, I’m sure).

Next on my agenda is the Lickable Wallpapers recipe. In an America’s Test Kitchen podcast, Felicity Dahl talks about how children would come out of a screening of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, begging their parents to buy some Lickable Wallpaper. Whenever my nephew watches the movie, I know I can be ready with some.

#Culture

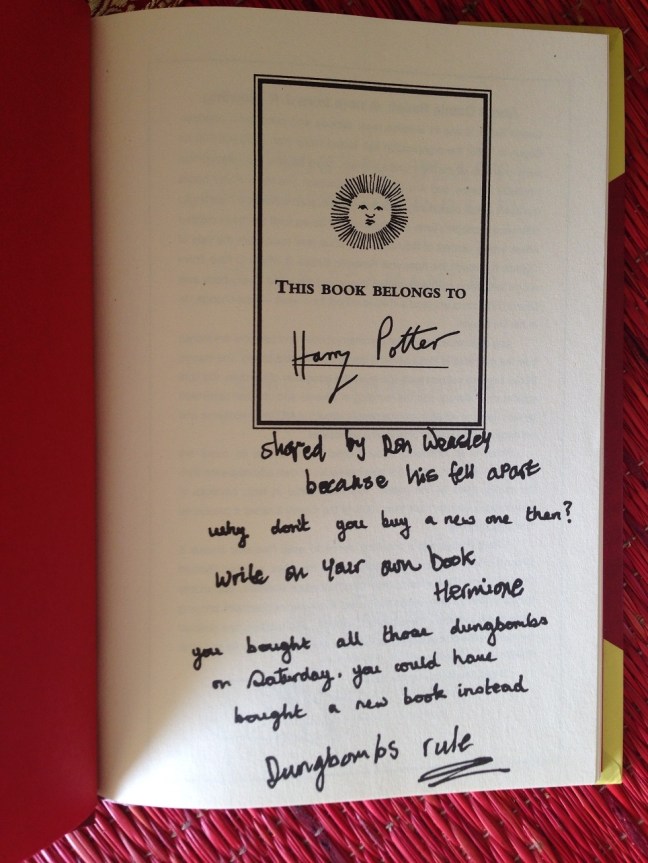

When Bijal Vachharajani is not reading Harry Potter, she can be found traipsing around the jungles of India. In her spare time, she works as a communications consultant and writes about education for sustainable development and food security so she can fund those trips and expensive Potter books.