http://www.thehindu.com/books/Goodfellas/article16966377.ece

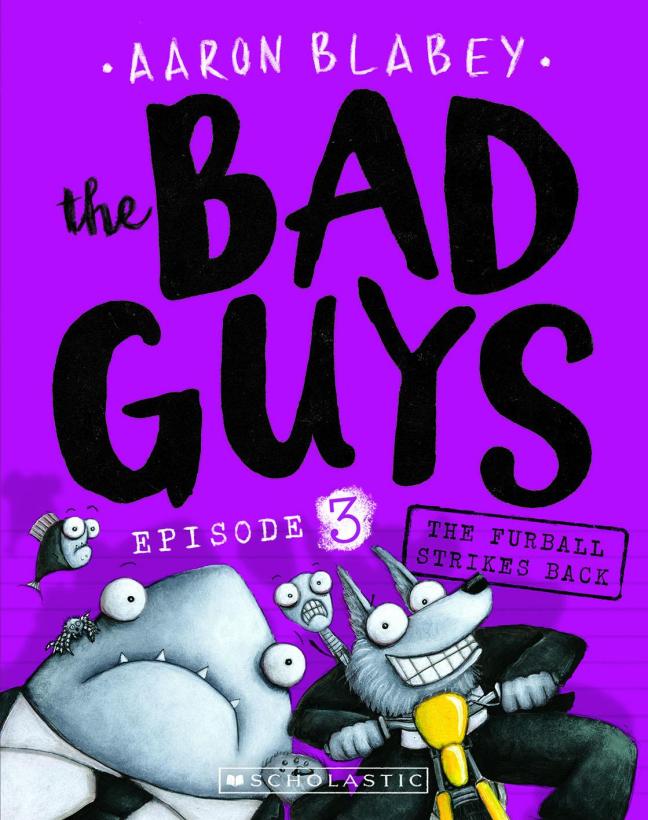

A wolf, a shark, a snake, and a piranha don suits and begin The Good Guys Club. No, that’s not the start of a joke, but the premise of Aaron Blabey’s The Bad Guys series published by Scholastic. The books are about a quartet who really really look like Bad Guys, in fact, everyone thinks they are terribly Bad Guys, scary and dangerous. But what they really really want is to be heroes, especially Mr. Wolf. Unfortunately, everyone keeps judging the Samaritans on how frightening they look, even the dapper suits don’t seem to help their image.

“I wanted to make something that my overly-sophisticated eight and 10-year-olds would think was cool,” said Blabey over email. “It was also a reaction to seeing a lot of deeply boring Early Reader books being brought home from school. Some books seem to have been designed to discourage children from ever wanting to read again. It was my hope to provide an antidote to that.”

Written and illustrated by Blabey, the comic chapter books are fully fun. Each page elicits a few chuckles, and some are simply laugh out loud. No surprise then that The Bad Guys has been extremely successful in Australia and is now available in India as well. “Kids really seem to love it,” said Blabey. “And kids who don’t like to read books are loving it too. THAT is the greatest thing that has ever happened to me. I’m immensely proud of that: kids who consider books to be Kryptonite are queuing up for the next instalment.”

But they are more than just funny stories. In Episode 1, The Good Guys Club sets off to rescue 200 puppies locked up in a maximum security city dog pound (their hopes and dreams are trapped behind walls of stone and bars of steel) and in Episode 2 – Mission Unpluckable, their daring plan is to rescue 10,000 chickens from a high-security cage farm (never mind that one of their members is a notorious chicken swallower). These are narratives that will be loved by animal advocacy champions. “It’s more about characters who’ve simply been judged their whole lives because of the way they look,” said the Australia-based Blabey. “The fact that they’re animals is inconsequential. One of them — Wolf — wants to transcend his situation. His counterpart — Snake — is resigned to it. Their polar approaches to handling this dilemma is the engine of the series.”

The Bad Guys explores attitudes and discrimination at the same time, using humour deftly to present the issues. “I find Wolf heart breaking,” said the bestselling author. “He can’t understand why no one can see how nice he is. The world’s preconceived notions of what the boys are is a rich and satisfying seam of material to mine and for the record, I love making this series more than I can say.”

Blabey effortlessly switches between writing and illustrating comic chapter books and picture books, including the adorable Pig the Pug series and Piranhas Don’t Eat Bananas. Blabey said that his approach to the books is completely different. “I walk when I write picture books. The rhythm of walking helps me write in verse. I walk until I have a book,” he said. “The Bad Guys, on the other hand, is written like a screenplay, sitting at a desk, on a Mac. The process of switching between them is like crop rotation (Joni Mitchell famously referred to moving between song writing and painting in the same way. I’ve stolen that from her.)”

As he walks about the Blue Mountains thinking up his stories, Blabey pens them down on phones and other such entities. “I like mediums of impermanence, like phones, white-boards and napkins, because they encourage naughtiness,” he said. “Handsome notebooks demand reverence. Every mark seems to diminish their beauty. My notes app, on the other hand, feels utterly transient, so I tend to be more relaxed and playful when I write on it. I love white-board too. Nothing is at stake, so I feel free to play.”