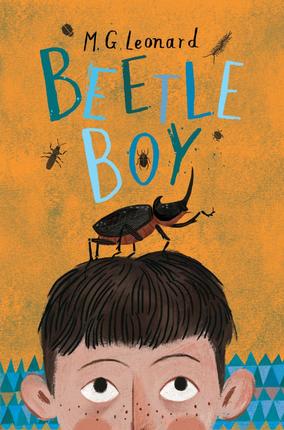

Maya G. Leonard’s fictional tale of a boy and the world of beetles is written with humour, warmth and respect

What happens when you’re terrified of insects? You write a book about them, of course. Or at least that’s what Maya G. Leonard did, and the result is the brilliant Beetle Boy (Scholastic), the first of a three-book series.

“I was writing a different story, about a villain who I imagined living in a place filled with insects, which I recognise now is a terrible cliché,” says Leonard, who lives in Brighton and works as a digital producer with the National Theatre in London. “Insects are often used to suggest a negative otherness,” she adds.

Fascinating insects

As Leonard began researching insects, she found herself fascinated by them. “I Googled different types of insects, to describe them accurately, and I was genuinely shocked when I learned about beetles and how adaptable, important and beautiful they are,” she says, in an email interview. “I don’t know if it was my own fear of insects, lack of education in the natural world or plain ignorance that meant I’d grown to adulthood without realising how wonderful these creatures are, but I was interested in that ignorance. I’m very ordinary, and I thought, if I didn’t know how essential beetles are to our ecosystem, then there is a good chance that most people don’t know. I decided to do something about my ignorance, something positive, and tell a story where the insects are the good guys.”

About a boy

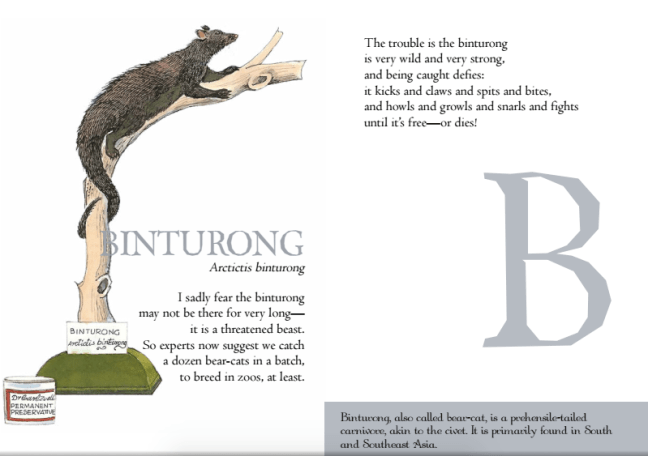

The book, Beetle Boy, is the story of Darkus Cuttle, a 13-year-old boy whose father suddenly disappears from his workplace, the Natural History Museum. The mystery deepens when Baxter, a clever rhinoceros beetle befriends Darkus. So many questions: how does Baxter understand Darkus, are these mysterious events connected with the evil Lucretia Cutter who has built an empire of insect jewellery, and can Darkus count on his new friends, Virginia and Bertolt?

Of course, Beetle Boy is a triumph in that it underscores the value of unlikely friendships and makes for a thrilling read. “Children’s hearts and eyes are open to the wonder of the world and they are slow to judge,” says Leonard. “The story had to be about children discovering the wonderful world of beetles because adult’s opinions are often already formed and resistant to change. At the heart of this story is the powerful relationship between a boy and a beetle, and the friendships he makes in the face of adversity. It is those friendships that give him the courage to be heroic and find his father.”

But what also makes it an unusual story is the manner in which Leonard conjures up a sense of wonder about arthropods. You can’t help but marvel at her descriptions of the stag beetles with their “monstrous antler-like mandibles” or frog-legged beetles with their cherry-red exoskeleton that shimmers as it moves, or wonder at dung beetles and Hercules beetles. There’s awe, humour, warmth, and respect in Leonard’s portrayal of beetles. Suddenly, you want to be out there, peering at every blade of grass, observing these beautiful, wondrous creatures.

“I did all of the research for Beetle Boy by myself, over four years,” says Leonard. “I read everything I could, watched every video, looked at a billion images and filled my head with beetles. I care greatly that I do justice to the beetles, and in writing about entomologists, I wanted to show the importance of the science and the work they do.” When Leonard got a publishing deal with Chicken House, she decided to get an entomologist to look at the story. “I wouldn’t have let it be published without a scientist approving of the content,” she says. “That’s how I met Dr. Sarah Beynon, who is a specialist in dung beetles and runs The Bug Farm in Pembrokeshire. She was amazing, and edited the book for factual accuracy, pointing out my rookie errors. For example, I’d referred to a beetle’s exoskeleton as a shell, which I corrected.”

Cast of characters

Leonard also throws in a handful of unforgettable characters: human and insects, one of the most compelling being Lucretia Cutter. “I love a good villainess, because they shock or frighten a reader by violently bucking the gender stereotypes of women as fragile, maternal or compliant,” says the writer. “For me, a great villainess has to have intense desires, a searing intellect and an intriguing glamour or mesmerising repulsiveness.

I knew before I started writing Beetle Boy that my power-hungry scientist and super-villain would be a woman. I named her ‘Lucretia’ after the infamous Lucrezia Borgia who has inspired many villainous incarnations and ‘Cutter’ for the tailoring job it describes, as well as the literal meaning of the word. There is nothing soft about Lucretia Cutter, she’s all malicious intent and sharp edges. I can’t say much more about her without ruining the story, but she will horrify you.

Respecting nature

A recurrent theme in Beetle Boy is respect for nature: there’s sinister genetics engineering at play, and at the same time, you realise how unique the insects are, without being tampered with. “When I was researching for Beetle Boy I discovered that humans have already genetically engineered insects, fruit flies and mosquitoes,” says Leonard.

“The debate around the possible dangers of meddling with genetics and the impact on the ecosystem interested me,” she says.

“I wondered what might happen if you genetically engineered the most adaptable creature on the planet, which is of course the beetle. As far as I know, there has been no genetic engineering of beetles, which left me free to imagine. I love the Frankenstein story and am drawn to questions of this nature, because there is no right or wrong, just responsibility and consequence.”

The second book in the trilogy, Beetle Queen, is slated to be published in April 2017, with Leonard promising that the “adventure gets darker, funnier, and travels further than Beetle Boy”.

If we were beetles, our antennae would be quivering with anticipation.

Three things you must know about the author

Favourite beetle

“My favourite beetle changes every week because with over 3,50,000 known species to choose from, it’s impossible to pick one. I find the tiger beetle very funny. A tiger beetle runs so fast it can’t see, so sprints in short zig-zag bursts and has giant bulbous eyes to orientate it when it stops.”

Writing stories

“I’ve always been drawn towards performed stories, and have worked with a rich variety of artists in my professional life from The Royal Ballet to Shakespeare’s Globe. I struggled with words and grammar when I was at school, which was why dance was the initial area of the arts that interested me, but as I’ve grown and become more practised with language my desire to write my stories down has increased, and I don’t mind admitting I’m proud of Beetle Boy.”

Once-upon-a-time fear of insects

“My fear of insects is important because I have come to realise that fear stems from a lack of understanding. It was an interesting challenge to use positive language to describe the insects because my brain initially gave me words with negative associations. In striving to think of the beetles positively, describing them as friendly and wonderful, I have somehow reprogrammed my own brain.

“A spider can still startle me, but I keep a pair of rainbow stag beetles at home now, and I love them. Perhaps if this book had existed when I was young, I wouldn’t have spent 20 years frightened of mini-beasts. The imagination is a powerful thing.”

Bijal Vachharajani writes about education for sustainable development, conservation, and food security. She’s the former editor of Time Out Bengaluru