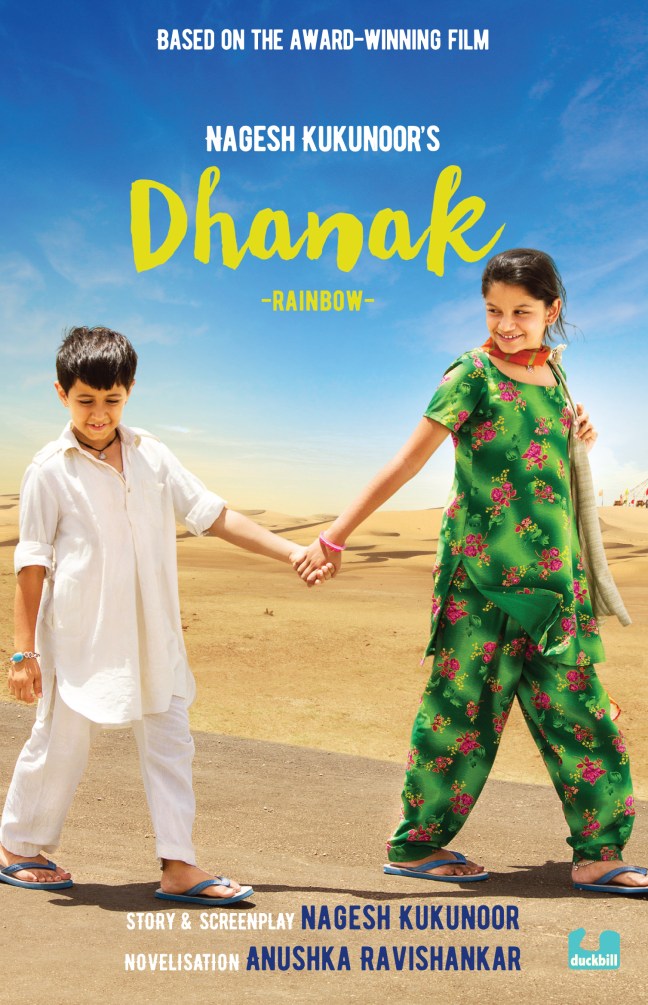

Nagesh Kukunoor’s new film Dhanak has been novelised by children’s writer Anushka Ravishankar

http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/mumbai/read-the-movie/article8623588.ece?ref=tpnews

All eyes are on Nagesh Kukunoor as the much-awaited film Dhanak is set to release next month. This time around, before they watch the film, children can now read the movie. Duckbill Books is publishing Dhanak ’s novelisation on June 10, a week before the film releases. The book is written by one of India’s beloved children’s books writers, Anushka Ravishankar, one of the founders of Duckbill.

“We’ve been seeing some really good children’s films in Indian languages,” said Ravishankar, over email. “and it has often struck us that the kind of stories being told in films are very different from the kind of stories that are written for children’s books: more experimental, more unusual. Some of those films would make wonderful books.” A friend told Sayoni Basu, Duckbill co-founder, about Dhanak . She then floated the idea to Elahe Hiptoola, one of the producers. “They were cautiously enthusiastic, and sent us a preview of the film,” Ravishankar says. “We saw it and thought it would make a great book.”

Dhanak ’s trailer already looks promising, and it has been garnering attention internationally. The story is about a pair of siblings who live in Rajasthan with their uncle and aunt. Pari is determined that Chotu will get his eyesight back before his ninth birthday, but that’s barely a couple of months away. Things look up when Pari sees a poster with Shah Rukh Khan urging people to donate their eyes. She starts writing letters to the actor, asking him to help Chotu. When Shah Rukh Khan comes to Rajasthan for a shoot, Pari and Chotu set off on a road trip, determined to meet the actor and get Chotu’s eyesight back. En route they encounter all sorts of people: some helpful, others kind, some horrid, and others mysterious. The book also includes eight pages of colour photographs and interviews with Hetal Gada and Krrish Chabria, the actors who play the siblings.

Ravishankar described the process of turning the film into a book for children as exhilarating and frightening. “It’s a very visual film, and Nagesh has captured both, the spectacular landscape of Rajasthan, and the joyous optimism of childhood. To translate all of that into words seemed like a daunting task. But since I’d never done it before, it was quite an exciting journey of discovery for me. I had to think about practical things like POV [point of view], because it works very differently in a novel as compared to a film. I also had to convert expressions and observations into interior monologue and description. I’ve never been very enthusiastic about describing things in my books, so that was quite a change for me!”

To write the book, Ravishankar spoke to Kukunoor a couple of times. “It was quite lovely. I spoke to him only a couple of times, but they were longish chats, about character, about specific plot points and timelines, what he felt the essence of the film was. He was helpful and forthcoming and I felt comfortable talking to him, even when I didn’t entirely agree with him! If I hadn’t felt that degree of comfort, I suspect it would have been harder to write the book.”

The story is all about moments: the banter between the siblings over Salman and Shah Rukh Khan, Chotu’s incessant demand for food, and the warmth and solidity of their relationship. Rajasthan is an intense, vibrant backdrop, its characters flitting in and out in all shades of grey and myriad colours. Unlikely friendships, the kindness of strangers, and preserving against all odds are themes woven into the plot.

Of course since Dhanak is a Bollywood film, there have to be songs. But Ravishankar manages to integrate them into the story quite seamlessly. “There’s the wedding party which the children join, and there’s the American man with whom Chotu sings and the Kalbeliya singers/dancers whom they sing with around the campfire. None of the situations are implausible. I ignored the songs that were part of the background score, of course!”

At some point, you forget that this is a novelisation of a movie; it’s easy to get lost in the story.

But then Ravishankar has written memorable children’s books such as Tiger on a Tree , Catch that Crocodile! , To Market! To Market! , and Moin and the Monster . Her mathematics degree has been put to good use in Captain Coconut & The Case of the Missing Bananas .

According to the Duckbill founders, Dhanak is the first Indian novelisation of a children’s film. In the past, K.A. Abbas has novelised Bobby and Mera Naam Joker , but there aren’t that many examples. And none for children’s films.

“Children’s films in India seem to be doing interesting things,” said Basu. “but it is really hard to track them down to watch! We still need many more diverse kinds of stories and voices in children’s books, and I do hope we can find them.”

Ravishankar says that one of the problems is that there are few spaces to exhibit children’s films. “Many of them don’t even see theatre releases, and if they do, they probably have one morning show on one screen! I think that is a crying shame. I wish schools would make the time and space for children to see good cinema. There are so many talented filmmakers making powerful children’s films. They need to be seen.”

The author writes about education for sustainable development, conservation, and food security. She’s the former editor of Time Out Bengaluru

The conversation brought back dabba memories, of going to school and opening my stainless steel lunch box in the afternoon, hours after it was packed, wondering about its contents. With the mother being a fabulous cook, the dabba was usually crammed with theplas folded in half with a dibbi of mango pickle, jeera rice with caramelized onion and curd, or rotis that miraculously stayed soft so that they could be torn with two fingers and eaten with sabji . There was lunchbox envy, where I coveted my classmates’ tiffins because they brought food that wasn’t familiar to me. I yearned for cucumber sandwiches, after re-reading Enid Blyton books, even though the white bread would be curling up at the edges by afternoon. I even wanted the dabba that held cold, clammy Maggi noodles, something that I now wouldn’t touch with a barge pole. But at that time, it was as exciting as moringa leaves are now to chefs.

The conversation brought back dabba memories, of going to school and opening my stainless steel lunch box in the afternoon, hours after it was packed, wondering about its contents. With the mother being a fabulous cook, the dabba was usually crammed with theplas folded in half with a dibbi of mango pickle, jeera rice with caramelized onion and curd, or rotis that miraculously stayed soft so that they could be torn with two fingers and eaten with sabji . There was lunchbox envy, where I coveted my classmates’ tiffins because they brought food that wasn’t familiar to me. I yearned for cucumber sandwiches, after re-reading Enid Blyton books, even though the white bread would be curling up at the edges by afternoon. I even wanted the dabba that held cold, clammy Maggi noodles, something that I now wouldn’t touch with a barge pole. But at that time, it was as exciting as moringa leaves are now to chefs.