The Man Who Loved STORIES: ABHIYAN HUMANE

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1553313634427_9849 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid { margin-right: -20px; }

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1553313634427_9849 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid-slide .margin-wrapper { margin-right: 20px; margin-bottom: 20px; }

Every time someone visits our house, their eyes are riveted to two focus points – one a gigantic mural painted by friends on our living room wall, and the second, rows and rows of books. History and social justice, picture books, YA and middle grade books, comics and graphic novels, crime, politics, the Ambedkarite movement, cooking and baking, pop-up books, design and art, environment fiction and non-fiction books. My late partner, Abhiyan Humane would nonchalantly walk up to a shelf, pull out a book and start talking about unsolved equations in its pages or the impact of weed on the brain (I’d have to hide the book later else he’d lend it out without my knowledge).

Abhiyan was made up of stories, some he inhaled from books, others he made up, the twinkle in his eye a foil to the serious expression on his face as his words spun themselves into narratives. I maybe the author, but he was the storyteller. His lectures at the Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology would often start with a talk about the stories that Early Man drew on the walls of caves and how storytelling has been core to our evolution.

Imagination cannot be learned

Telling stories through his exhibition in Goa

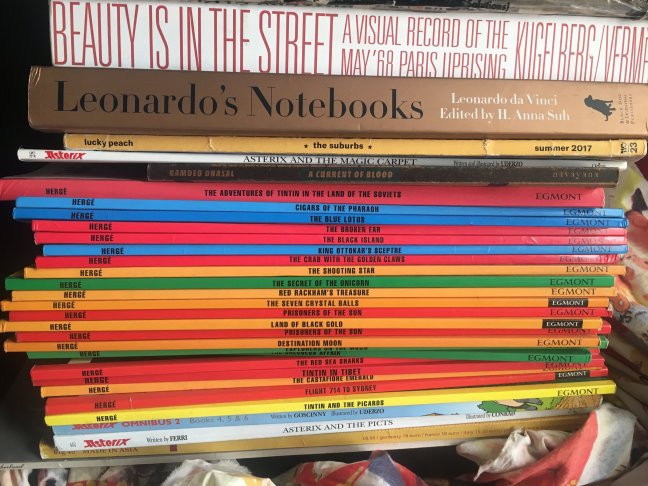

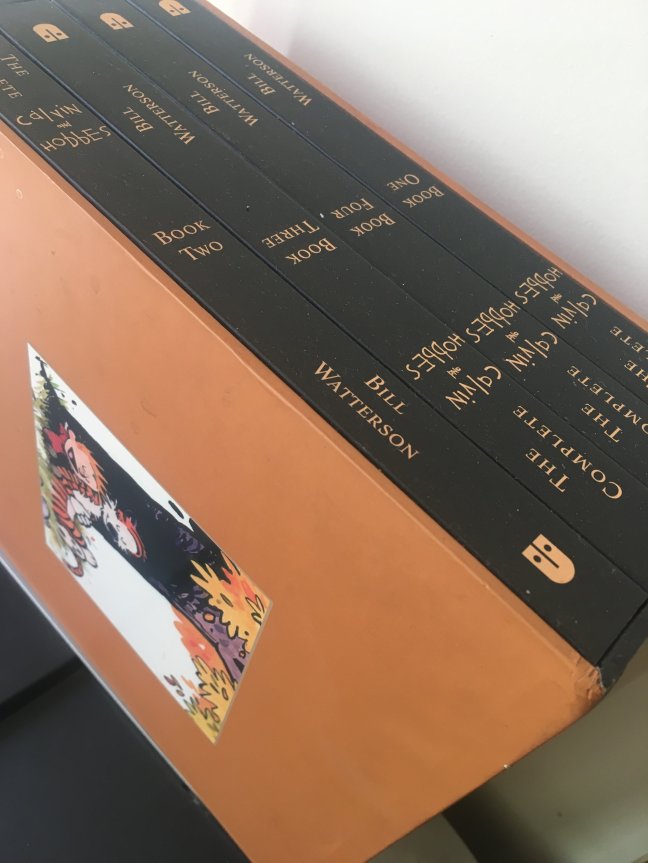

Growing up in Mumbai, books were the bricks that Abhiyan used to build a fort to meet head on the abuse, neglect and treatment that the many-headed dragon of caste battered upon him. Comics (and Russian writers, apparently) were the armoury of that fort – where Asterix, Calvin and Hobbes, and Tintin ruled. In fact, once we moved to Bangalore, with no savings and new jobs, we started re-building these comic collections from scratch. I’d go to Blossom Book House after every salary SMS and buy one precious Tintin. And the rest of the month would be spent re-reading it. His birthday gift, the entire Calvin and Hobbes set, stayed next to Abhiyan’s bed for the rest of his short life.

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1553317922305_22415 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid { margin-right: -20px; }

#block-yui_3_17_2_1_1553317922305_22415 .sqs-gallery-block-grid .sqs-gallery-design-grid-slide .margin-wrapper { margin-right: 20px; margin-bottom: 20px; }

In early 2000, Abhiyan headed off for a Masters in the USA – we’ve spend hours over Skype outraging that The Case of the Exploding Mangoes did not win The Man Booker Prize or he’d ask me to explain for the 169th time, why did I read Harry Potter again and again. He never did end up reading the Potter books, but Abhiyan would often put on the films during dinner and then laugh when I’d parrot the lines under my breath or chuckle at my gasp at a familiar plot turn. He wasn’t a reading snob – he happily traded Narcopolis for The Diary of a Social Butterfly and Percy Jackson’s Greek Gods (nothing to do with his friends calling him Greek God, of course), but it was science that had his heart – books about the cosmos, math, raptors, trees.

I should have figured what our seventeen years together and not-together would entail, when Abhiyan’s first gift to me was Nineteen Eighty-Four. To Abhiyan the world was dystopian, one where privilege and entitlement obstinately kept the scales tipped, plunging the other side into a nightmarish darkness of inequity. His last few years on this planet was spent addressing that. Along with Anoop Kumar and Mangesh Dahiwale, he set up The Nagpur Collective, a national network of young Ambedkarite scholars, activists, students, academicians and professionals.

As that friendship deepened, Mangesh wrote about one such evening that they spent talking about the collective, their work and the world. “As we talked through come finer points, he took control of music and started playing a sequence of songs on his iPhone. He started with Nina Simone (this was the first time I heard this name) ending up with “The Revolution Will Not be Televised, through James Brown’s “Sex Machina”, sprinkling Bob Marley and Fela Kuti in between, he set us free.” A musical pattern well known to his students and colleagues who spent hours on our balcony, talking and/ dancing.

Anoop told me that when Abhiyan first visited him at his Nalanda Academy in Wardha, a space where he helps prepare young adults for college life, they talked for hours. And when Abhiyan left, he sent Anoop a message, “I have ordered some chairs for your students.” Because then Anoop was teaching in a Buddha Vihara half-equipped with a few chairs and floor rugs. Little did anyone of us know that space was to become Abhiyan’s calling.

He went back in 2016 with a bunch of his colleagues and students what would become the start of Nalanda Labs. By day four of the summer camp, forty children were coming to the Buddha Vihara to tinker with electronics, computers and of course stories. By the time Abhiyan wound up the camp, it had been home to over hundred children and young adults in the relentless summer heat. There’s a video on YouTube where Abhiyan is lecturing the children while carefully opening a Pratham Books Library-in-Classroom Kit about respecting and loving books, handling them with care and concern, and owning them. As he finished opening the package, he gently pushed the children in front, asking them to open it. Their hesitant hands opened the kit, gasping at the books, a smile flitted on Abhiyan’s face. Go on, he urges, open and read.

<div class="sqs-video-wrapper" data-provider-name="" data-html="